Exhibits The NAEB's Programs for the Disadvantaged

In March 1968, the final report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, commonly referred to as the Kerner Commission Report, was published and read by millions of Americans. Following a string of race riots in the summers between 1964 and 1967, President Johnson had established the Commission to investigate the issue of civil and racial unrest, and answer three questions: “What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again?”

The report did not provide pretty answers to these questions, nor did it propose easy solutions. Blaming systemic racism and white culture for its ignorance, disenfranchisement, and marginalization of African Americans over time, it recommended widespread reforms and investments in job creation and training as well as housing. Johnson, under enormous pressure to end the war in Vietnam and feeling slighted after having passed the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, largely ignored the report. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated in April, which just snowballed the country’s racial tension and civil unrest and led to further riots.

All of these factors contributed to a feeling of urgency to address our country's huge racial inequities. The title of Chapter Fifteen of the Kerner Report was “The News Media and the Disorders.” The strategies that the media employed to not only cover race and poverty, but to invoke empathy and social understanding was immediately resonant with all areas of the news and broadcast media, and educational broadcasting jumped enthusiastically on that train.

The NAEB papers contain an April 1968 letter from Win Griffith of the President's Council on Youth Opportunity to Chalmers Marquis, head of NAEB’s Educational Television Stations (ETS) division, about his thoughts on what educational television can do to help 'establish more constructive attitudes' in America's cities. By May, the NAEB announced the formation of two committees to “examine the role of educational broadcasting regarding programming and employment practices for minority groups.” The initiative was called Programs for the Disadvantaged, and its director was led by Kenneth A. Clark from the Metropolitan Applied Research Center (MARC). One committee operated under the auspices of National Educational Radio and the other under Educational Television Stations (divisions of the NAEB), with each reporting back out to NAEB leadership and member stations.

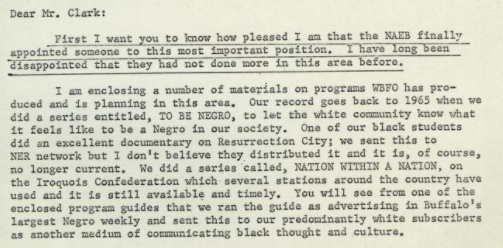

Between roughly June and September of that year, Clark and his team began a campaign to gather and disseminate information from and between member stations requesting that they return reports about both their programming for urban and rural audiences. Throughout July and August, stations replied to him with reports of varying enthusiasm. Some expressed great interest, proudly listing copious numbers of radio and television series and other programming aimed at urban and rural audiences:

Others replied with a mix of defensiveness or apprehension, expressing regret at the lack of programming they had on which to report, and citing low demand in their communities for such content:

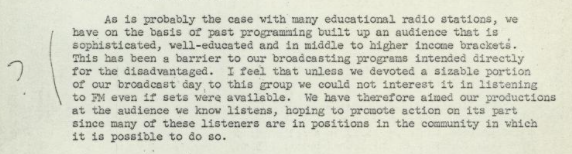

Clark did not wait for all reports to come in before disseminating their contents back out to NAEB leadership and membership; he began issuing weekly reports to both radio and television station members almost immediately, highlighting content being produced and programs being undertaken to encourage training and employment for minorities. Clark’s rhetoric in these reports is infused with an enthusiastic rallying cry of sorts for member stations to take inspiration from them and begin rolling out more and more programming, playfully encouraging self awareness, transparency, and modesty with a splash of guilt. In one humorous example, Clark cites a KUOW (Seattle, WA) report where station manager Ken Kager defined a categorization of potential programming sources. In his definition of one category, ‘Non-Local,’ Kager expresses humility and lightly jabs at his ‘up-tight’ listening constituency:

By highlighting quotes like this Clark’s modus operandi is apparent. The reports encouraged that stations who did not have the funds, wherewithal, or interested audiences to make their own original programming for, by or about minority audiences should still make use of the NAEB’s radio network to contact the stations who did, and consider hosting their content as ‘Non-Local’ programming, the socially responsible logic being that even if these programs didn’t immediately seem reflective of the concerns of a station’s direct community, they were still organically important to the national conversation as a whole.

On the other end of the ‘national conversation’ spectrum as covered in the NAEB’s records on Programs for the Disadvantaged is the topic of increased training and education opportunities for underrepresented groups to work in educational broadcasting. Earlier reports were more heavily focused on programming, with some exceptions such as American University’s Urban Broadcasting Workshop. There is also an acerbic letter from activist, academic and noted media critic Dave Berkman to former NAEB President William Harley, in which he pushes Harley candidly (among other things) on ETV’s “failure to serve its black constituencies.” The Eighth Report of the Radio Programs for the Disadvantaged by Project Director Ken Clark in October 1968 focuses almost exclusively on training initiatives, employment, and minority representation by NAEB television and radio stations, including an appendix featuring a list of 37 key individuals in various key educational broadcasting roles (from producers to hosts to engineers) across the country.

The NAEB’s collection of audio programs held by University of Maryland is far from comprehensive in terms of representing the vast amount of their distributed content, but two full radio series which were featured and highlighted as part of the Programs for the Disadvantaged are linked below. One of these is The Negro American, a radio lecture series by Professor Benjamin Quarles of Morgan State College, Baltimore, made in late 1967 in Detroit Public Schools. The series covers one topic each week, starting off by posing the question 'Why Study Negro History?,' walking through slavery and abolition, the civil war and reconstruction, and contemporary protests.

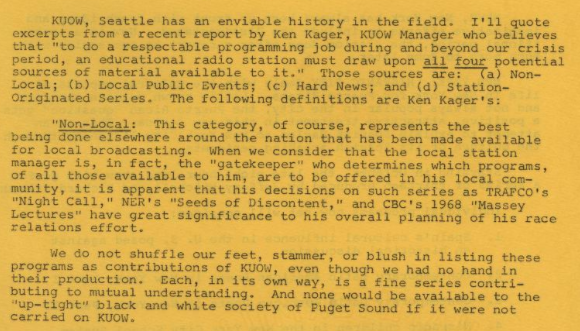

The second is the series Seeds of Discontent, which was written, produced, and hosted by Hartford Smith, Jr. and WDET out of Wayne State University in Detroit. Professor Smith contacted the Unlocking the Airwaves team and was gracious enough to grant an interview in which he discussed in depth the history of his social activism work working first with juvenile delinquents in Detroit through the court system. Smith was an avid and vocal critic of media coverage of social issues at the time, stating strongly that it did not reflect the real concerns of the everyday people he dealt with in his work. A friend who worked as an engineer at WDET connected him with the station and he successfully pitched the series Seeds of Discontent, which he worked on in the evenings for no pay after his social work job ended. He had connections with the community through his work and conducted hours of interviews with people about their lives, their opinions on contemporary issues. The result was 26 half-hour episodes which are fully transcribed and available on the Unlocking the Airwaves website.

As an extension to this exhibit, this list compiles information on all radio and television series mentioned in the NAEB Programs for the Disadvantaged correspondence. Select programs are available online externally to the Unlocking the Airwaves website.

* A transcript of the recorded interview with Hartford Smith, Jr. can be viewed here. To view a video of the recorded interview, click here.

Director for Programs for the Disadvantaged Dr. Kenneth B. Clark (Chicago Urban League Records, University of Illinois at Chicago Library). CC BY-SA 3.0 "

Series documentation for "Seeds of Discontent"

Press Image of Hartford Smith, Jr.

Cover image for "The Negro American: A Documentary History," edited by Leslie H. Fishel, Jr. and Benjamin Quarles. Quarles would later give radio lectures produced by Detroit Public Schools on the same topic, which were distributed by the NAEB.