Exhibits Inventing a Service: How Educational Radio Became Public

In 1967, backers of non-commercial radio won a great victory. Four years after losing its major financial supporter, the Ford Foundation, reformers saw the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 was signed into law, creating the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Although initially intended to address television only, last minute efforts by educational radio veterans and handwritten and scotch taped additions to the bill expanded its focus to include radio broadcasting in the corporation’s remit. (Mitchell 35) Now however, the rag-tag group of educational broadcasters who had worked tirelessly with scant funds for decades had to develop an actual service and it some ways, their legacy hurt them as much as it helped them.

The backdoor lobbying by educational radio “guerillas” (as longtime public radio executive Jack Michell described them), alienated sectors of educational broadcasting that saw television as the future. The staffers who had pulled off the coup, Jerry Sandler and Edwin Burrows would be ushered out of national public broadcasting positions and would spend the rest of their careers in much smaller locales. But it was not simply ruffled feathers that educational radio was up against. It was also their own reputation for producing dull, highbrow programming.

Although recent research into the output of educational radio convincingly argues that there was no single type of radio voice for educational radio in the 1950s and early 1960s (St. John Et. Al. 2023), contemporaneous studies of listening habits from the reinforced educational radio’s reputation for an orientation toward eggheads. For example, Herman Land’s 1967 study The Hidden Medium found that the audience tended to prefer classical music programming that aired in the evening (Land 1967). At a moment when Great Society reformers in and out of government wanted to serve under resourced minorities rather than an older, educated, and affluent audience the rebranding of educational radio into public radio has not been given much historical attention. Newly digitized materials from the National Association of Educational Broadcasters and the American Archive of Public Broadcasting help shed a light on this crucial moment for non-commercial radio broadcasting in the United States. The materials in the Broadcasting AV website allow users to not only match up the written documentation with programming, they also facilitate tracing the discussions and debates of these radio reformers. This exhibit looks at a crucial transition period, when the educational radio community – both practitioners and policymakers – were grappling with their identity as it related to a new set of parameters, “public” broadcasting.

With the previous leadership of the National Association of Educational Broadcasters out, the organization looked for new leadership. The Chairman of its Board of Directors, John Witherspoon looked to a different Washington, this time the state, for that new direction. There, in Pullman, a veteran educational broadcaster named Robert A. Mott was well ensconced as the news director for KWSU-AM and the chief writer for a weekly educational radio program called “Science in the News.” This show was part of educational radio’s bicycle network, airing on over 50 stations and the Voice of America. In part because of the success of that show and in part because Mott was tabula rosa in DC, he was approached for and took a position as the executive director of National Educational Radio, part of the NAEB, in late Summer 1968. (Powell 2022; Harrison and Harrison 1978 2-3) It is worth noting that, unlike Sandler and Burrows, neither Witherspoon nor Mott appear as entities within professional networks tracked on the Broadcasting AV Data website. There is a small collection of Mott’s materials at the University of Maryland but it is separate from the Broadcasting A/V Data website. Likewise, Witherspoon appears only via his participation in the Public Radio Oral History Project. Likewise, as I will discuss below, during this transitional period, Mott regularly corresponded with Donald Quayle. Quayle was the former executive director of the Eastern Educational Broadcasting Network and had been hired by the CPB in November 1968 to serve as a consultant as they developed their plans for public radio. Quayle is also not tracked by the Broadcasting AV site, although there are significant holdings connected to him via his role developing radio drama for WGHB, WHA, and that were generated by his role as the first President of NPR. Their separation reinforces the divide between the NAEB and Big Ten university dominated era of educational broadcasting (which comprises much of the Broadcasting AV Data website), compared to the public broadcasting era that followed.

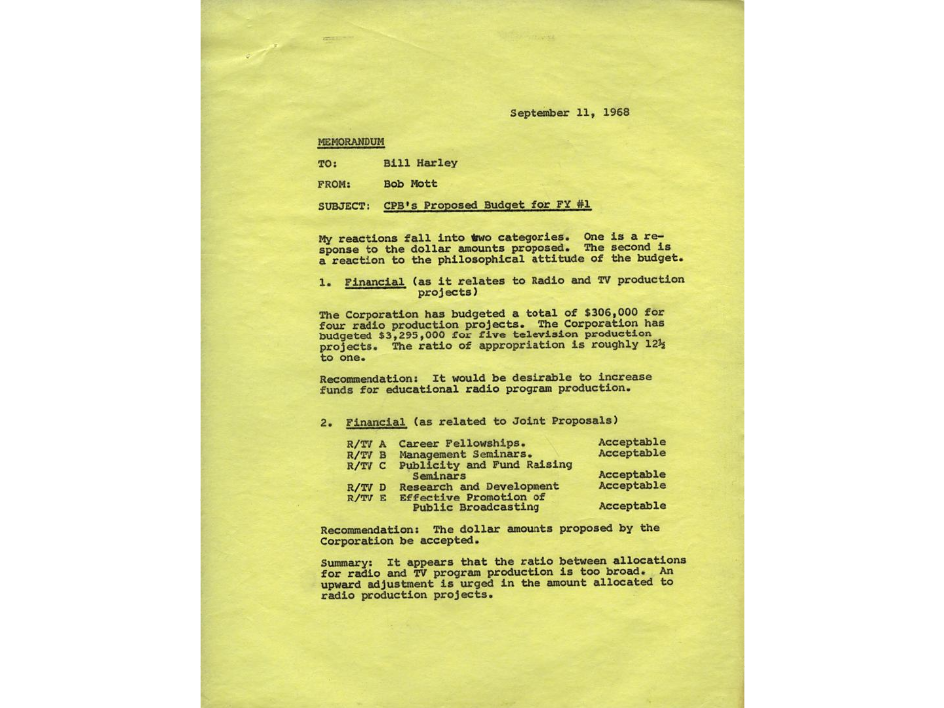

In his new position, Mott was tasked with articulating a vision for public broadcasting, which meant addressing the elephant in the room, educational radio’s reputation. In the wake of the passage of the Public Broadcasting Act, the CPB was having a difficult time squaring its legal mandate to fund public broadcasting with the variety of non-commercial, educational stations. Essentially, they worried how they would support over 400 stations, some of which were fairly large and professionally oriented but others of which were small, lower powered and run by students. Moreover, it was unclear whether those stations had enough professional, creative, and financial depth to create a new. The budget allocations from the CPB were 12 ½ to 1 in favor of television and the budgeting documents contained negative comments about the status of educational radio and their ability to serve their communities (Mott to Bill Harley September, 11, 1968).

Bernard Mayes, the General Manager of KQED (who also had a varied background as an Episcopal worker priest, teacher, journalist and soon to be first Chairman of NPR) produced a report on the proceeding of the Suffern Conference on Public Radio held jointly by the CPB and the Ford Foundation in October 1968, entitled “Programming for Public Radio: Some Preliminary Considerations.” Mayes' position as an English émigré and experience as a journalist with the BBC gave him an outsider’s perspective on American educational broadcasting:

“The conflict is at is most apparent during questions of financing – Should money be spent beefing up existing programs, or should it go to build and entirely new service assuming on to be possible? Such a question carries with it the unwritten agendas both of already existing organization still struggling with devotion to the cause of ‘educational’ [quotes in original] radio, and also of those for whom this cause appears lost and who would like something new. The principles of ‘public’ radio would seem to cut the knot. For whereas, ‘educational’ radio has been, and presumably will remains largely concerned with the academic interest of its limited catchments, ‘public radio must, by definition, relate to public needs. This means the audience of the latter would hopefully be the entire community. This returns us to the original concept of true educational radio in its broadest sense.”

Mayles was not sanguine as to the feasibility of this goal: “It is suggested that if the present system were beefed up, it would be ready to revest to this original concept itself, but the specialised [sic] objects and private loyalties of nearly all existing stations as they have historically develop make this extremely doubtful, if not impossible.” The question for Mayles was whether to consider a “Patchwork” or “Comprehensive” approach. The latter represented a “beefing up” of existing institutions but would be easier. The latter would require something more transformative and therefore, more difficult. Reflecting on this position, Mott felt that Mayles’ premise that educational broadcasting had been primarily concerned with narrow interests to be flawed. However, he also found the overall conclusions convincing, programming would be central but the task of best utilizing old and new resources and institutions would be the challenge.

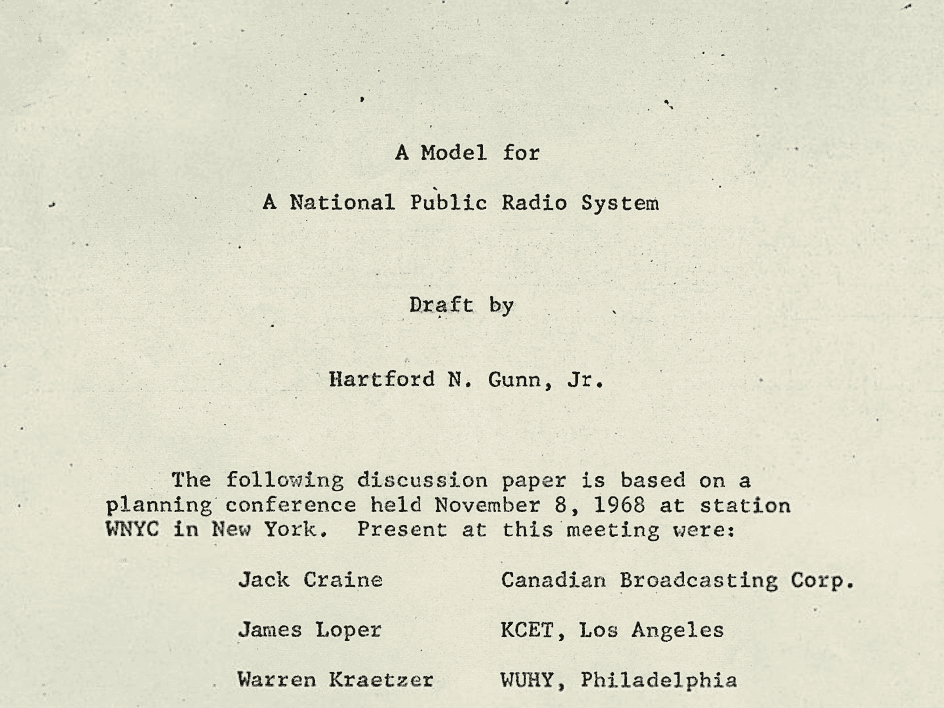

Aiding these deliberations were a number of studies of the status of educational broadcasting. While there had already been some fairly extensive research (Land’s study was only a little over a year old) the Corporation for Public Broadcasting undertook several surveys, studies, and proposals. One was commissioned by CPB’s Secretary-Treasurer, veteran broadcaster Robert Swezey. Swezey in turn, hired Sam Holt, a recent Harvard grad whose father owned a CBS affiliate in Birmingham, Alabama, to conduct a study of educational radio. Holt is also not tracked by the Broadcasting AV site, although there are extensive records of his consulting efforts contained in the University of Maryland Special Collections. At the same time, another part of the CPB Board, its radio committee, hired long-time educational radio broadcaster Allen Miller, to do its own study. Finally, Harold Gunn, the head of Boston station WGBH would articulate his own vision for a National Public Radio System in a presentation to other educational broadcasters in November 1968 entitled, “A Model for a National Public Radio System.” While Miller and Gunn are both tracked by the Broadcasting AV website, the vast majority of documents address their activities in during the era when the dominant paradigm was Educational Radio rather than Public Radio. Their contributions during this transitional period are found in folders reflecting the correspondence of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. (See https://www.unlockingtheairwaves.org/document/naeb-b093-f01/ and https://www.unlockingtheairwaves.org/document/naeb-b093-f02/) Additionally, while there is documentation of Mott reaching out to Miller in December 1968 to have him attend CPB meetings to present his findings, it is not clear whether he did so and the bulk of the discussion tended to be around Gunn’s proposal.

After establishing the context of commercial and educational radio in the United States, Gunn was unsparing in his assessment of the latter, noting: “For the most part, these efforts are severely limited by lack of resources, both creative and financial…Many education radio stations have little distinctive character or sound, in too many cases lack of funds and commitment produce inferior or amateurish programming.” The solution, he argued, was to bypass the smaller stations in favor of five to eight key affiliates that would produce programming a signature “sound.” “Need for a clearly definable character, or sound. Just as listeners can pick our certain rock and roll stations the minute, they tun to them, so must listeners be able to identify this sort of programming in a flash.”

As Josh Shepperd (2023) argues regarding an earlier period of educational radio reformers, commercial radio was not merely a foil, but was also a source of programming and policy ideas. “One of the ways educational radio can be useful and significant on a national basis is to develop a service of tightly-formatted, in-depth national and international news and public affairs, with the emphasis on analysis, commentary, criticism, and good talk, with variety supplied by “actualities,”, performances, and experimental productions which would explore the sound media in terms relevant to the present” (Gunn). Gunn took his cues from commercial radio to reproduce a notion of station identification via production style, humor, musical jingles and other audio techniques. Gunn also proposed an aggressive schedule for creating a national network and providing programming for it.

Mott acknowledged many of the positive aspects of Gunn’s proposal and concluded that “it merits support” (Mott to Richard Catalono Dec. 6, 1968). However, he had some significant reservations. In his response, circulated in January 1969 to various figures in the public broadcasting policy world, he wrote: The suggestion that “listeners must be ablet to identify this sort of programming (public radio ) in a flash” is desirable but impractical. We would agree with the concept that the programming must have a character and, if possible, a “sound”. It would seem that audience will be established by an extensive promotional effort rather than “sound” (https://www.unlockingtheairwaves.org/document/naeb-b093-f02/#115). In addition, while he agreed with the need for an interconnected network, he proposed a larger, more dispersed group of stations (ten versus five to eight in the Gunn proposal) and a more gradual introduction of programming. “Initiating a public radio service on a nine hour per day level minimum (as proposed) would create an economic and cultural shock that would prove detrimental to long range goals“ (https://www.unlockingtheairwaves.org/document/naeb-b093-f02/#118). Instead, he proposed more modest goals in the amount of programming. Starting with four hours a day by July 1969, he proposed adding at least four additional hours of programming a day until full 24/7 operation was reached by 1971.

Mott circulated his response across the public media policy community, but altered his standard cover letter when writing Gunn in what seems like an effort to ensure that his critique would not be received negatively: “It is interesting, I think, that the problems stem not from the ultimate goal but rather from the means to accomplish the goals. Your model and my reaction to it are at widely separated points in the spectrum. Perhaps, after additional reaction and review, there should be further discussion among those interested.” (Mott to Gunn, Jan 14, 1969).

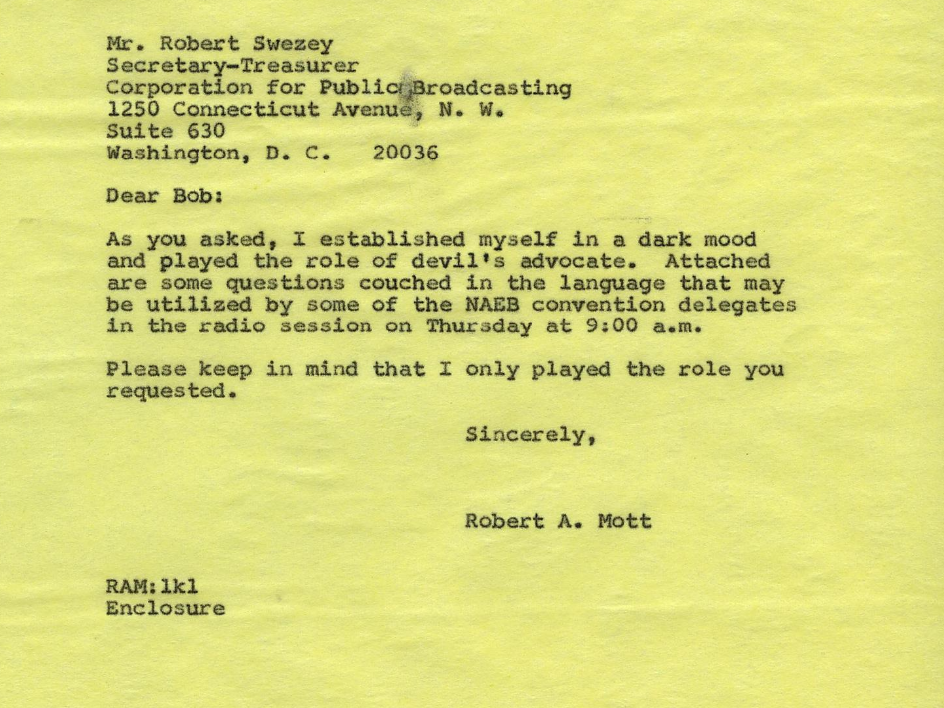

In addition to responding to Gunn’s proposal, Swezey tasked Mott with developing talking points for CPB to use at the NAEB convention. The former seemed to anticipate some aggressive responses by the educational broadcasters. As Mott noted in a cover letter, “As you asked, I established myself in a dark mood and played the role of devil’s advocate…Please keep in mind that I only played the role you requested” (Mott to Swezey Nov. 15, 1968) Mott anticipated that the educational broadcasting delegates would demand to know the status of the CPB’s radio efforts – financially, administratively, strategically – all of which they believed were lagging behind the attention being given to educational television.

In the interim, Mott busied himself with those areas in which there were agreement, specifically, the need for a national programming center and the bracketing off of smaller stations. The first task involved moving educational radio’s tape duplication center from its longtime home in Champaign, Illinois to Washington, DC which planned and completed during the Spring and Summer of 1969. (Mott to Quayle Jan. 23 1969). During that same period, Mott responded to a charge to establish criterea for interconnection among non-commercial stations, given to him by Donald Quayle, who was acting as a general consultant for the CPB (Mott to Qualye Jan. 17, 1969).

Mott’s criteria evolved over time, but even in its early incarnations while it “will be built on the foundation provided by existing stations and state or regional networks” it envisioned a far smaller group than the 400 operating educational stations. In “A Plan for Establishing an Educational Radio Network” Mott listed 39 stations in 25 markets as “key stations.” The next tier involved another 97 stations, variously identified as “optional” or “secondary.” Key threshold criteria for inclusion were a minimum of 240 days of annual operations and minimum daily operating hours (double the time provided by network programming). These criteria would functionally eliminate many smaller, student run stations.

A month later, the criteria began to emerge. In letter to Quayle on Feb 26, he noted: “At our Feb 14 meeting in Mr. Swezey’s office you asked that I prepare a document citing criteria by which non-commercial radio stations might be more precisely identified.” Noting that the following was his personal opinion rather than one of the organization, he argued that “NER current policy is to accept in membership any non-commercial licensed station who applied for membership. I think this policy unwise and will recommend at some future time, that we define our membership requirements more precisely. This is virtually mandated by the diversity of factors related to educational radio broadcasting” (Ibid.). While he hoped that the Miller and Holt studies would address this, the idea that the CPB should fund all educational stations on an equal basis was “sheer folly.” He suggested six criteria:

- Transmitter power - more than 10 watts

- Coverage area

- Licensee status (he largely excluded religious and student government license holders)

- Presence of professional rather than student staff

- Consistent operating schedule (staying on the air during semester breaks)

- programming philosophy - “If, in fact, the station acknowledges that it is serving a limited public or a selected audience without intending to serve a variety of publics covering a spectrum of the community, it would not qualify for CPB support (Ibid., 55-57).

By early Spring 1969, a proposal to the CPB Radio Advisory Board noted the acute need for “a precise identification of a ‘public’ radio stations. Until public radio is adequately defined, the corporation is faced with the task of supporting all stations in equal fashion. This appears impractical.” (Mott to Macy April 8, 1969 re March 20-21 meeting of the CPB Radio Advisory committee) Also during this time, Mott began putting the descriptor “public” in quotes as a way of distinguishing stations that met his criteria from those that didn’t. With this, the institutional separation of educational from public radio was put into motion.

On one hand the legacy of these efforts is longstanding. In the intervening years, distinctions among community, college, and public radio stations have been mapped onto these criteria. Particularly for those who were outside the professionalized stations, the concessions involved in gaining legal status or justifying one’s license came with pressure to professionalize and a perception that they may lose what they perceived as their unique ability to reach out to communities not represented in the public sphere. Radio historiography is full of these debates. But on the other hand, the origins of the split between community, educational, and public has not gotten similar amounts of scholarly attention. The story of Robert Mott has gone largely untold because, like the smaller educational stations, he too was put on the outside of a public radio community that desired greater professional status.

While Mott had defined a core group of public radio stations, he did anticipate the desire of public television to excise themselves from radio. The 1969 NAEB Convention split public broadcasting into PBS and NPR. NPR formed a governing board tasked with choosing a leader. In May of 1970, it had come down to two individuals, Mott and legendary journalist and critic Robert Lewis Shayon. Shayon bio excerpts. By Mott’s telling, this reflected a board that “hadn’t done its work…Shayon is one sort of person, and I’m another sort of person.” Indeed, the board deadlocked at six to six. When informed of this, Mott pulled his candidacy because he didn’t want the job without uniform support. After a time, he lent his support to his old boss, Don Quayle, who had been angling for a job with PBS but lost out to Herbert Gunn. Quayle became the first President of NPR and Mott moved over to PBS, where he worked as the director of station relations for the new organization and, later, for the Public Service Satellite Consortium.

---

Secondary Source Bibliography

Harrison Burt and Dee Harrison, “Oral History of Robert Mott, Public Radio Oral History Project,” 1978, University of Maryland Special Collections, College Park, MD

Land, Herman, The Hidden Medium: A Status Report on Educational Radio in the United States, Herman W. Land Associates, 1967.

Powell, Albert, “KWSU Radio (Pullman),” 2022 https://www.historylink.org/file/22416

Shepperd, Josh. Shadow of the New Deal: The Victory of Public Broadcasting. University of Illinois Press, 2023.

***

Alexander Russo is an Associate Professor in the Department of Media Studies at The Catholic University of America in Washington. He studies the technology and cultural form of radio and television, the development of “old” new media, the history of music and society, and the history of popular culture.

.](/static/fa22ef0859fb348acaebe99d1aba63a0/5d2f6/2016spring-mott-4-e1454093460354-1188x828.jpg)

Robert A. Mott at KWSU. WSU Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections.

A Model for a National Public Radio System, Hartford N. Gunn, Jr. https://www.unlockingtheairwaves.org/document/naeb-b093-f02/#131

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Public Broadcasting Act on November 7, 1967. Yoichi Okamoto, LBJ Library.