Exhibits The Global Politics of American Culture and the English Language: A Voice of America Survey

Radio programming, by its collaborative nature, connects people—in networks that can be easily mapped, but also in less visible, or inaudible, networks. Radio’s writers, broadcasters, producers, volunteers and other staff leave archival traces of their work in recordings, financial documents, correspondence, and so on. How many listeners a radio program reaches, and who they are, can be harder to track.

The design and exploration of radio archives with a “network … lens, as opposed to a content… lens,” which the Broadcasting A/V Data project hopes to encourage, is appealing for many reasons. The ways an archive presents and organizes itself influences what can be discovered within it. Those interested in the history of public radio, community radio, and educational radio—including students and the general public—may not know quite what they are looking for, or what they might find. And those of us with specialized disciplinary expertise may deny ourselves new pleasures and transformative insights if we approach archives with a narrow focus. If we explore radio archives with patience and open minds, as the BAVD project affords opportunities to do, we may uncover some of the hidden networks that radio creates, and voices of radio listeners we might not otherwise hear from.

As a case in point, I will share my exploration of the 240 pages listed under “Poetry Project Voice of America 1963-64,” which 1) is not primarily about the Poetry Project; 2) contains terse, revealing insights on the global politics of the English language and American culture, amid the Cold War and ongoing decolonization, from 77 radio stations all over the world, in response to a Voice of America questionnaire sent out by the well-known news broadcaster, who had becomes Director of the United States Information Agency, Edward R. Murrow.

As a scholar of American poetry and digital voice studies, I am perhaps not a typical user of the BAVD archive. When I have done archival research in manuscripts (at Vassar College, Harvard’s Houghton Library, Dartmouth College, etc.), I have typically looked at correspondence and drafts of poems. My research in sound archives has almost always focused on poetry recordings. With the Entities search approach to the BAVD database, I was not sure where to start.

A “poetry” search , brought 8 hits, including familiar poets and writers I have written about and taught (Robert Frost, Aldous Huxley, Archibald MacLeish, Robert Penn Warren, and Walt Whitman), a radio producer (Robert Lewis Shayon), a professor and poetry scholar (Anthony Ostroff, whom I mentioned in another piece for Unlocking the Airwaves), and a minor poet (Christopher Darlington Morey). Exploring these pages, I found that Penn Warren was involved in an eight-part program called “As others read us: American fiction abroad,” with the Literary Association of the University of Massachusetts, supported by a grant from the Educational Television and Radio Center and “in cooperation with the [NAEB].” This made me think of American literature abroad, which inspired me to search for the “Voice of America”. No hits.

For fun, I searched for “National Public Radio,” which the NAEB preceded: 25 hits, mostly specific radio stations. This could facilitate the history of a local radio station. Mine was KCFR, in Colorado. No hits. I searched for “Literature”: 25 hits, but no one I am studying these days. One could do a thorough study of the archive to see who was most represented among American writers on public radio programming in a particular era. I then searched for the names of Black women poets, for a collaborative book project I’m working on. No hits. They may not be indexed yet, or they may not be represented in the archive.

Cheating, I went back to the Unlocking the Airwaves, searched for “Voice of America poetry,” and came upon the 240 pages titled “Voice of America Poetry Project 1963-64.” Though the first pages do include that title, the documents encompass much more than a one-year VOA poetry programming project. Unfortunately, there do not seem to be any recordings associated with it. (If I had tried to discover the same items through the BAVD database, I would have had to search via entities and individuals involved, and as a literary scholar, I probably would not have known their names.)

While some documents relate to the poetry project, some of the most fascinating pages detail the creation of and planning for “English-by-Radio,” a pedagogical program that apparently flourished enough to survive today. As of 2023, the Voice of America continues to offer “Learning English,” which its website says began as “Special English” in 1959: “Special English newscasts and features were a primary fixture of VOA’s international shortwave broadcasts for more than half a century. In 2014, our line of products was expanded to include more English teaching materials, and the service became known as Learning English.” No mention is made of English-by-Radio on the VOA website.

Page 20 of the VOA Poetry Project materials begins with a contract between the United States of America—specifically the U.S. Information Agency (founded by President Eisenhower in 1953, and absorbed into the U.S. Department of State in 1999))—and the NAEB. It projects “A series of thirty-nine (39) fifteen minute scripts at the intermediate level, dealing with intonation, pronunciation and rhythm,” following “A written prospectus outlining a graded sequence of language structures in 15-minute broadcast programs from the elementary through the advanced level … based up on that found in the USIA-NCTE publication, ‘English for Today.’ ” The contract also included “A series of 13 analysis-commentaries on poems for the Agency’s projected ‘English through Poetry’ series.”

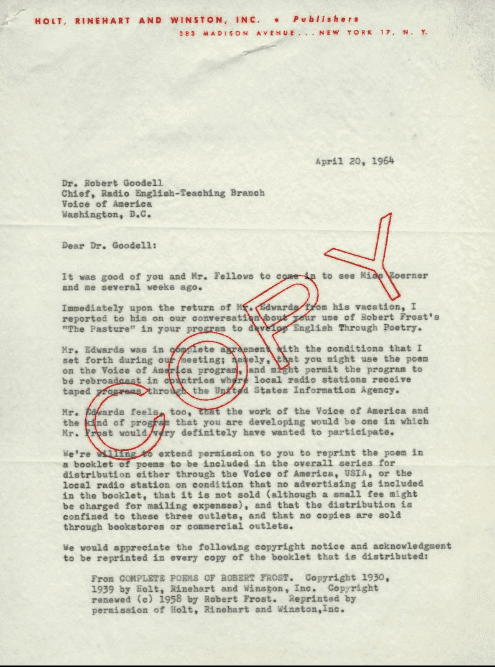

Early on, the documents are mostly letters from one James A. Fellows (listed as as a radio executive in the BAVD database via the Entities search option, with 23 linked documents, including the Voice of American Poetry project) to various publishers, requesting permission to to include particular poems in broadcasting and print materials.

As a typical permissions letter explained, “In each script the poem will be read in its entirety, and the listeners will also be invited to read the lines aloud in appropriate units after the radio speaker.” Additionally, permission was requested to possibly “use the poems on the Voice of America program, and … permit the program to be rebroadcast in countries where local radio stations receive taped programs through the United States Information Agency,” and to print the poems in a pamphlet to be distributed to interested listeners.

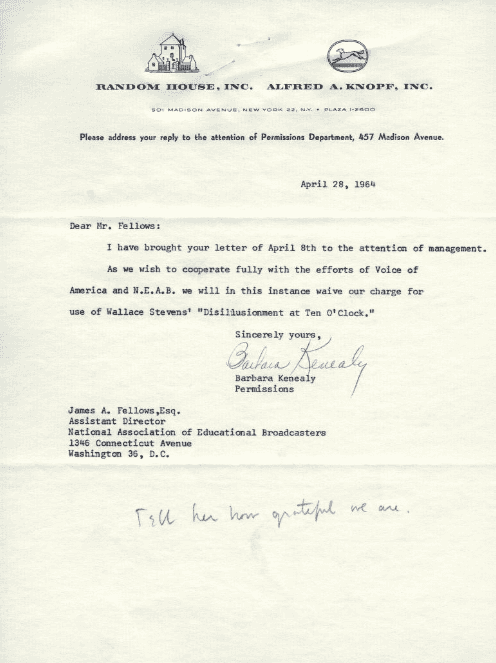

The choice of some poets struck me as odd, given the goals of teaching English by radio. They included some High Modernist American poets (H.D., Wallace Stevens, Marianne Moore, Hart Crane, William Carlos Williams)—and William Butler Yeats, obviously not an American. These are not especially accessible poets for English language learners. Others were more popular—Frost, E.A. Robinson, Vachel Lindsay, Carl Sandburg, Richard Eberhart. But the poets listed toward the end of the document, for whom copyright permission was not required, were no easier—Emily Dickinson—or were not American, or might sound archaic for an English language learner in 1963—Byron, Tennyson, Longfellow. How, I wondered, were these choices made, beyond the tastes and judgment of the eminent critic and Columbia University professor M.L. Rosenthal, who was hired to create the 13 scripts?

Something of an answer began to emerge around pages 197-199. In order to plan this program, a long memo dated Feb. 11, 1963, was sent by “air pouch”— a secure diplomatic telegram system used by the U.S. Dept. of State, to “All USIS posts with English teaching activities, and American Embassy Warsaw (FROM RUSK),” and copies “for information only” sent to “USIS-LONDON, USIS-CNBERRA, AMERICAN EMBASSIES MOSCOW AND PRAGUE (FROM RUSK), AND AMERICAN LEGATIONS BUCHAREST, BUDAPEST AND SOFIA (FROM RUSK).

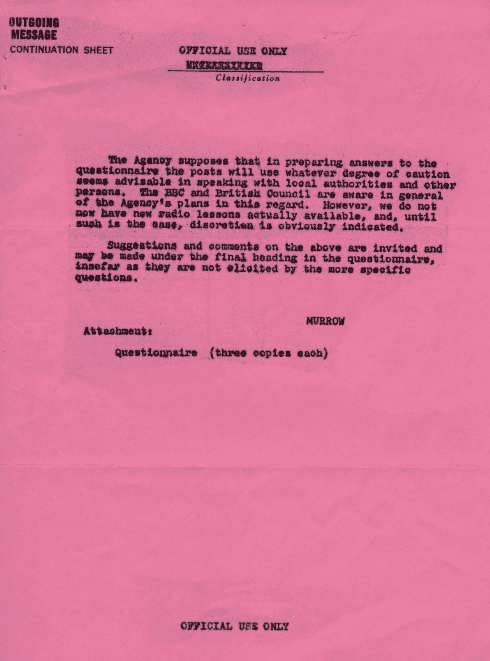

As the memo explains, which is simply signed “MURROW” :

“Several months ago the English-by-Radio Branch was established within the Central Program Services Division of IBS. The task of this branch is the planning, preparation of production of radio English-teaching courses, primarily for local placement, but also for VOA broadcast. The Branch will also provide guidance and materials to the field posts…. Such plans must take into account information that can be supplied only by the field. Therefore, the cooperation of the posts in answering and returning the attached questionnaire will be much appreciated.”

The “field posts” here refer to radio stations all over the world that broadcast VOA programs. The term “field” has since undergone considerable postcolonial critique, for marginalizing and exoticizing the “field” of the global South, against the presumed “home” of ethnographers in Europe or the U.S. In the 1950s and 1960s, of course, many countries in Africa and Central and Latin America were in the process of liberating themselves from European and American colonial rule. The memo continues, advising caution amid local political conditions that “the posts” must navigate, in gauging interest in English-language instruction by an American-sponsored radio program:

“The Agency supposes that in preparing answers to the questionnaire the posts will use whatever degree of caution seems advisable in speaking with local authorities and other persons. The BBC and British Council are aware in general of the Agency’s plans in this regard. However, we do not now have new radio lessons actually available, and, until such is the case, discretion is obviously indicated.”

The questionnaire included:

“Question 1: Of what potential usefulness and importance would you consider radio courses to be as part of the USIS English teaching efforts in your area?”

“Question 8: Do you consider predominantly American cultural material in the lessons would, if carefully selected, be interesting and meaningful to listeners?”

- • Conary, the capital of Guinea (independent from France in1958), responded thus to Question 8: “No. Material should be adapted to make it meaningful and interesting to African listeners.”

- • Cotonou, a city in Benin(independent from France in 1960), responded: “Some Americana OK, but how about some African too? It would beat out the BBC.” Dar es Salaam, in Tanzania(independent from Britain in 1961), simply said “No, it would be suspect.”

- • Khartoum, the capital of Sudan(independent from Britain and Egypt in 1956), responded: “Yes, especially if periodic comparisons made between Arabic and American cultures.”

- • Mexico City: “Inherited, unthinking resentment against U.S. so some resistance to Americana. Use it anyway.”

- • Tripoli, capital of Libya (administered by France and Britain after WWII, independent in 1951), simply responded: “No.”

- • Vienna gave a qualified response: “Yes, if not obviously propagandistic or too self-congratulatory in tone and nature.”

To question 1, Managua, capital of Nicaragua(independent from the U.S. in 1933), gave a skeptical response: “Limited use as part of USIS teaching services. 70% illiteracy here.” Port-au-Prince, capital of Haiti, felt differently: “With 85-90% illiteracy rate, radio teaching is most important.” Oslo: “No use. Norwegians do an excellent job themselves.”

Comments and suggestions on developing the English-by-Radio program imply shifting cultural alliances and the VOA’s efforts to compete with the BBC, and the U.S. to compete with the U.K, for global influence in the postwar era:

- • “Baghdad: Urge go-ahead. Far more merit in this program than some other current VOA activities.” “Bonn: Courses would not be accepted, nor are they needed.”

- • “Brazzaville [capital of the Congo, independence from Belgium: 1960]: Don’t want to antagonize British. BBC course only cultural activity they have in this country. Only approach C.A.R. authorities if agreement satisfactory to British is worked out.”

- • “Cairo: Long-felt need for new and better English material for the Arab world. We are ready, willing and able to assist.”

- • “Dar es Salaam: No priority can be given to English programs…. New, national emphasis on Swahili mitigates against English.”

- • “Libreville: Must convince British that our objectives are the same.”

- • “Mexico City: Good clear American English pronunciation, with neutral Spanish (no river Plate or Cuban accent) if tapes are made for Latin America."

- • Usumbura, now Bujumbura, the capital of Burundi (independence from Belgium, 1962: “French-English; cheap attractive printed te[x]t; deal with things and situations familiar to Africans. SHOULD NOT BE DULL!”

Would these varied audiences have found the poems chosen for the Poetry Project dull? The poem generally seem inoffensive, as if the VOA heeded requests to avoid explicit propaganda championing American values. But they often imply democratic, individualistic and revolutionary values, and the biographical sketches of the poets sometimes extol such values explicitly. A sketch of Wallace Stevens, whose anti-convention poem “Disillusionment of Ten O’Clock” was featured, is laughably described as “not influenced by other poets.” Emily Dickinson is represented by a poem that expresses the thrill of rebellion:

I never hear the word “Escape”

Without a quicker blood,

A sudden expectation –

A flying attitude!

Byron is represented by the sentimental “So We’ll Go No More a Roving”—but his biographical sketch emphasizes his service in the Greek Revolution. Richard Eberhart, a war hero in World War II, is represented by “For a Lamb,” which describes crows feasting on the rotting carcass of a lamb. One none too subtle choice was Sandburg’s 1920 poem “A.E.F.,” which stands for American Expeditionary Forces, and which hopefully predicts a future in which “a rusty gun on the wall / …. will be spoken among half-forgotten, wished-to-be-forgotten things.” The poem conceived in the hope that the Great War would be the war to end all wars works well as a Cold War vehicle.

How the “field posts” responded to these poems or the Poetry Project we do not know. But considering these choices in the context of the VOA global survey is valuable. Though in a far less flashy way, American poetry was considered a soft power tool along the lines of Abstract Expressionism, whose promotion with support from the CIA we are more familiar with. Discovering these poems within this larger VOA context pushes us to think of them not as individual literary achievements, but as American cultural capital circulating the globe.

Ideally, archives should provide maximum flexibility and intuitive paths for exploration, which might fall outside traditional content-driven disciplinary boundaries like literary or poetry studies. People and Organizations, the nodes of networks that one can explore with an Entities search in the BAVD network, promise the possibility of such exploration, though more people and organizations need to be indexed, and ideas of who and what might be relevant may continue to expand. When I came across the Voice of America Poetry Project, the Voice of America, the United States Information Agency, the U.S. Information Service, M.L. Rosenthal and Edward R. Murrow were not yet among the organizations or people indexed in the BAVD database. I am grateful to have participated in this exploration, and the development of the Entities search tool. I believe they can lead us to consider the reception of radio programming in surprising networked contexts, including previously invisible or unheard listeners.

***

Marit MacArthur is a Continuing Lecturer in the University Writing Program and a faculty affiliate in Performance Studies at the University of California, Davis. In 2018-19, she co-directed Tools for Listening to Text-in-Performance, funded by a NEH Digital Humanities Advancement grant.

President John F. Kennedy Attends Swearing-in of Edward R. Murrow as Director of the USIA. March 21, 1961.

Abbie Rowe. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston. https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/JFKWHP/1961/Month%2003/Day%2021/JFKWHP-1961-03-21-E

Letter to Dr. Robert Goodell regarding the use of Robert Frost's poetry in the Voice of America Poetry Project. April 20, 1964. https://www.unlockingtheairwaves.org/document/naeb-b100-f04/#52

U.S. Information Agency Memo regarding the English-by-Radio program, signed by "MURROW." February 11, 1963. https://www.unlockingtheairwaves.org/document/naeb-b100-f04/#199

Letter to James A. Fellows regarding the use of Wallace Stevens' poetry in the Voice of America Poetry Project. April 28, 1964. https://www.unlockingtheairwaves.org/document/naeb-b100-f04/#42