Exhibits Marshall McLuhan and the Understanding Media Project

Ideas in Action: Marshall McLuhan, the NAEB, and the Understanding Media Project

One notable but understudied chapter in the history of the NAEB involves the organization’s collaboration with the Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan. In the late 1950s, just as McLuhan’s profile was beginning to grow, the NAEB commissioned him to perform a study regarding the potential educational uses of new media and the implications of emerging media for education at various levels. Upon securing a grant from the National Defense of Education Act, the NAEB and McLuhan embarked upon a year-long project that resulted in a report entitled The Report on the Understanding Media Project. Although the report was not well received at the time, the papers in the NAEB collection pertaining to the project provide a substantial degree of insight into McLuhan’s working process and the evolution of his ideas pertaining to the media and education.

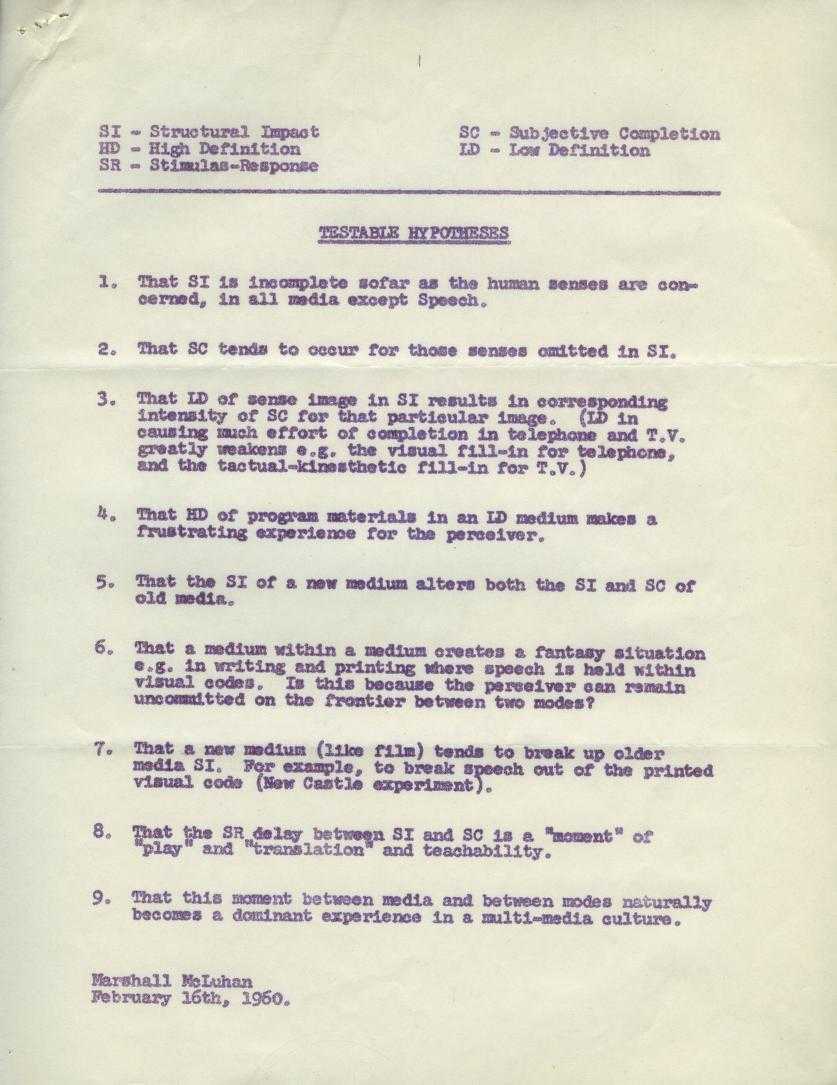

As Josh Shepperd (2011) illustrates, the project was not considered to be a success within the organization. While NAEB personnel recognized McLuhan’s genius and intellectual vitality, the documents reveal that they consistently struggled with his approach. They had difficulty getting him to convert his abstract, and at times chaotic, theoretical formulations into the sort of concrete research questions, hypotheses, and experiments that would produce results that would meet the criteria of the grant. As is detailed in Shepperd’s study, the project was ultimately terminated early with McLuhan’s final report being quietly processed by the NAEB’s administration and the whole affair quickly fading from view. However, despite the manner in which the affair was regarded at the time, the title of the project provides some clues as to its importance for its principal figure. Indeed, the work that McLuhan did in the lead-up to the grant application, and then on project itself, helped to establish the basis for his landmark 1964 book Understanding Media as well as The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962).

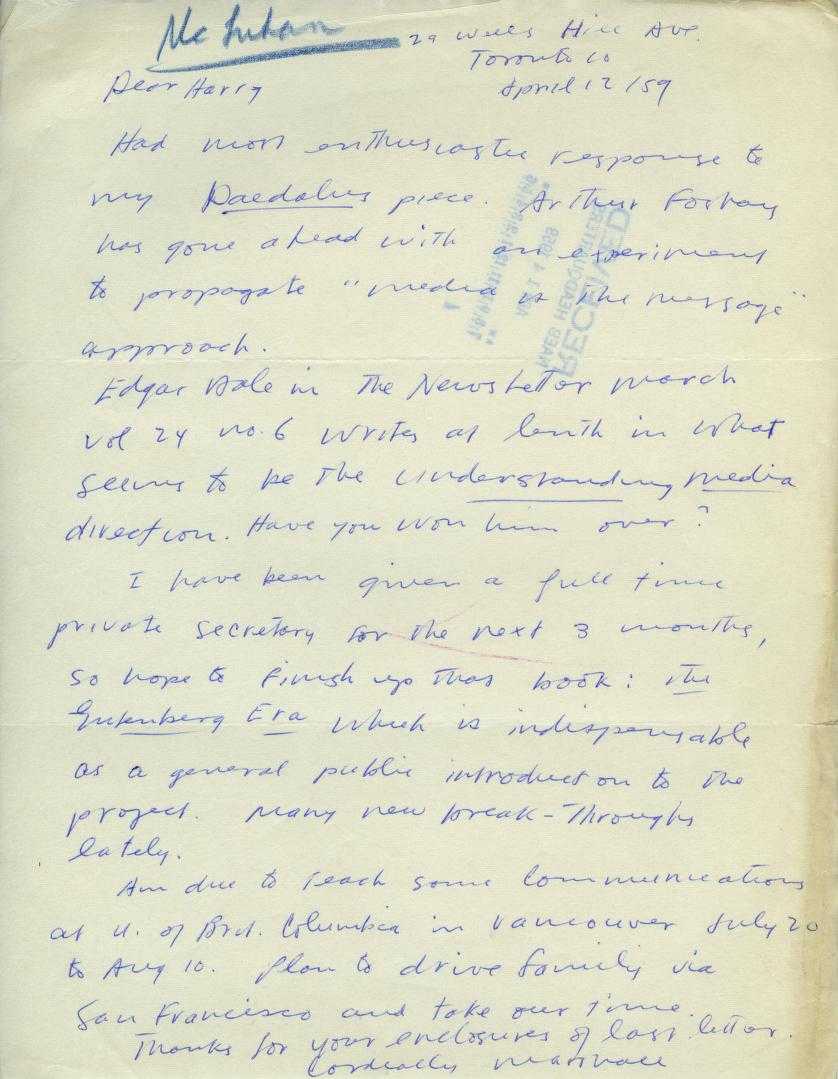

In his public appearances and published work, McLuhan often presented elliptical observations and aphoristic snippets of insight through an effervescent, rapid-fire approach characterized by the revelation of a multitude of ideas in quick succession. This is, after all, a man who reportedly frustrated his colleagues at the University of Toronto by evaluating student work not on the basis of its quality, but on the quantity of new ideas presented (Marchessault, 2004: 158). Certainly, his correspondence with respect to the NAEB project reflects these values. What is more, as McLuhan’s exchanges with NAEB Executive Director Harry Skornia and others illustrates, McLuhan’s theories evolved gradually out of their statement and restatement. The evidence of this process is particularly notable as McLuhan was not so invested in ‘showing his work’ in the public presentation of his ideas.

McLuhan’s letters and reports in the NAEB collection illustrate the gradual evolution of his theories pertaining to media. While it is not always possible to parse the precise circuits of influence, it is apparent that McLuhan’s ideas were influenced to some degree by his involvement with the NAEB. The organization’s leading figures were knowledgeable recipients who variously provided receptive ears for McLuhan’s musings, suggestions for the refinement of his ideas, new avenues or individuals to contact, or even healthy skepticism regarding his methods and conclusions.

The ideas expressed and developed in the documents largely pertain to key two key areas of interest: the media themselves and the evolution of educational practices and institutions in the face of the emergence of electronic mass media. In the area of the former, McLuhan’s correspondence and report drafts are studded with what he often terms ‘breakthroughs,’ incipient forms of the insights for which he would shortly receive such renown. For example, a letter to Skornia dated March 14, 1959 discusses detribalization and retribalization via the electronic mass media, alluding to the ways that these dynamics unfold in our “electronic global village.” In June of that year, McLuhan submitted a progress report that discussed light and lightbulbs at considerable length, presenting the idea that the lightbulb is a sort of medium without content, which would subsequently be elaborated upon in Understanding Media (1994: 8). The relationship between various media and their contents was an ongoing concern. In a letter dated June 5, McLuhan presents a new idea: “Media are ‘ideas’ in action. That is, any technological pattern or grouping of human know-how has the mark of our minds built into it.” This leads him into the revelation of “another basic fact: Men never have conscious grasp of any media until it has been translated into another medium.” In this observation, we see the essence of McLuhan’s famous observation that the content of a medium is invariably another medium.

Given the NAEB’s explicit focus on educational broadcasting, it is not surprising that McLuhan’s work with the organization tended to focus on the relationship between media and formal and informal education. Arguably one of the most notable breakthroughs detailed in the correspondence is McLuhan’s observation that the key point with respect to television is the way that light works through it, as in a stained-glass window. This notion would later be developed in the television chapter in Understanding Media (1994: 313). In a March 27 letter to Skornia, McLuhan makes a telling analogy between the light through/on dichotomy and the role of the media in education. In this instance, McLuhan seems to be observing that the key point of his project will be not to educate students about the new electronic mass media, but to develop an understanding of how education occurs formally and informally through the mass media (and thus how these media forms shape our lives and our collective lifeworld). Indeed, McLuhan consistently makes the point that the pupils in the educational environment will often have a more intuitive grasp of newer media forms than their instructors thanks to the informal education they’ve received in the private sphere. In part for this reason, McLuhan sees a gradual blurring of the traditional roles in the classroom: “…In terms of those teaching and learning it means that more teaching and that more learning will occur at much higher speed, and that the dichotomy between teacher and student (as between producer and consumer in industry) will fade away.” In keeping with this shift, McLuhan also avers that the old textbook-based model of assembly/lecture transmission-based learning will be on the way out as the new media era demands a dialogue-oriented approach. In a November 30, 1959 report, McLuhan provides a fascinating description of the reception of his ideas on the part of a group of Toronto high school teachers who were slated to participate in some project-related educational experiments:

The suggestion that there should be two teachers in class-room, in order to give stress to dialogue and learning, rather than to teaching was a suggestion they are prepared to consider but which is kind of bewildering to them. Since the new media have a kind of essential dialogue built into their electric technology, the textbook oriented class-room is widely at variance with new media. Even when using new media in the class-room, the assumptions of older media are unconsciously presented at various levels.

The extended quotation above exemplifies the way that many of McLuhan’s education-related observations about the new media could also apply to our current networked digital media paradigm. In fact, the insights found in the NAEB documents often illustrate just how far ahead of his time McLuhan was in terms of his media theories. As a result, the documents not only provide crucial insights into the evolution of his theories, they also help us to understand why McLuhan’s ideas have come back into fashion in recent decades and to appreciate how they may yet help us to understand our rapidly evolving media environment.

References

Marchessault, J. 2005. Marshall McLuhan: Cosmic Media. London, UK: Sage.

McLuhan, M. 1994. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Originally published in 1964.

Shepperd, Josh. 2011. Medien miss-verstehen. Marshall McLuhan und die National Association of Educational Broadcasters, 1958-1960. Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft. Heft 5: Empirie, Jg. 3: Nr. 2, S. 25–43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/2605.

Christopher Cwynar

.](/static/422b1c7c0bace848d039da7c9405e7c7/a5765/640px-marshall_mcluhan-2.jpg)

1945 photograph of Marshall McLuhan by Josephine Smith. Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

A 1959 letter from Marshall McLuhan to NAEB Executive Director Harry Skornia.

A 1960 list of testable hypotheses for the project by Marshall McLuhan.

detailing a speech given by Marshall McLuhan at the Conference on Educational Television and Related Media.](/static/896e461aeb653ce0144eeaafa2bcf6ff/e741f/naeb-b111-f08-06.jpg)

July 1958 NAEB newsletter detailing a speech given by Marshall McLuhan at the Conference on Educational Television and Related Media.